Kolkata and Dhaka – an intertwined history

Evolution and Planning of Two Cities on Water

Text: Das, Partha, Kolkata; Rahman, Mahbubur, Dhaka

Kolkata and Dhaka – an intertwined history

Evolution and Planning of Two Cities on Water

Text: Das, Partha, Kolkata; Rahman, Mahbubur, Dhaka

The two megacities Dhaka and Kolkata share a common language, geographical proximity and an intertwined history. Nevertheless, they seem reluctant to draw near each other. The fact that both are riverine cities owing much of their development to the rivers may help to build a bridge between them.

Bengal, the area comprising nowadays Bangladesh and West Bengal – and the largest delta in the world, confluence of the Ganges and Brahmaputra – has an extensive hydraulic system of water bodies, symbiotically related to the lives and habitats of the people living there. Given the tropical climate, topography and fertility of the soil, it has been confronted with natural calamities, but also building and expanding of settlements throughout its history. Starting from the 7th century BC, all historic cities that grew in this area were situated on the banks of rivers; their demise often owed to dwindling trade due to shifting river course. Dhaka, Bangladesh‘s capital and largest metropolitan conglomeration, and Kolkata, West Bengal‘s main city and India‘s third most populous agglomeration, both with around 13 million inhabitants in the metropolitan areas, need to be looked at as part of this context.

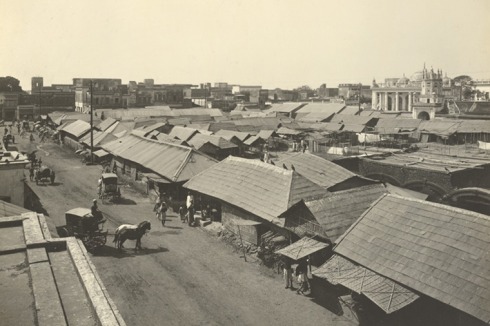

52 mosques and 40 canals

The region of Dhaka developed under Buddhist and later Hindu rule from the 7th century on and was then governed by Muslim sultans. The urban settlement, described in medieval reports as a “town of 52 mosques and 53 lanes”, attained a prominent role in 1610 by becoming the capital of Bengal, then the richest province of the Mughal Empire. Surrounded by rivers and wetlands, the city was strategically located with a high and fertile hinterland, a functioning river-canals communication system, and geographic centrality. This prompted Governor Islam Khan to shift the capital there to be able to better control the province. Connected by rivers with two other nearby historic settlements, Dhaka then flourished as a centre of artisans, manufacturing and river-based trade. In those days, easy access from the sea made the city attractive for merchants from China to Europe, trading in textiles, hide, handicraft, rice etc. So it should not come as a surprise that early 17th century visitors described it as a cosmopolitan city, and that by the end of the same century population rose to 200,000.

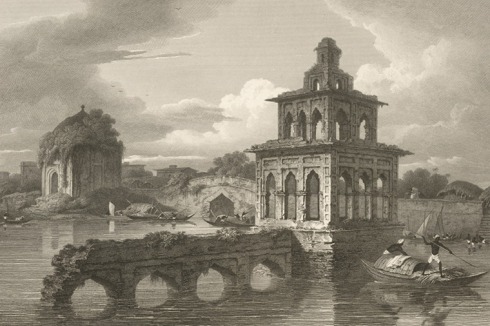

The historic city used to be criss-crossed by more than 40 khals, or canals – the means of communication, transportation, and storm drainage –, of which many were natural, others dug on order of the rulers. The over 250-km-long network of rivers and canals improved the city climate, protected it from floods and eventually shaped the city life. There were many bridges that are now-extinct; carpenters living nearby the water bodies used to build beautiful vessels and battleships. Until the colonial period, boats were the prevalent means of transport, and the rivers‘ serenity used to attract the elite to spend the summer on houseboats.

During the Mughals‘ reign, Dhaka was defended by eight successive riverfront forts. The ruling class settled in the areas surrounding the oldest fort, outside the existing mixed-use core of the town perched between the River Buriganga and a the Dulai Khal, a major canal flowing in west-east direction parallel to the river. Whereas institutional, civic and residential functions developed towards the north and east, the beautiful villas of the local elite as well as the increasing number of European businessmen dotted the riverfront, hiding the slums, alleys, forests, marshes, mosquitos and diseases behind. Thus early Dhaka rapidly grew in east-west direction corresponding to the flow of the Buriganga. The first two major roads were one parallel to the river and the other, connecting the main river terminal to the business district, perpendicular to it. This well-developed water-backbone influenced the socio-economic and cultural life of the city. Remarkable relics and majestically ornate civic, religious and residential buildings from both Mughal and British periods like Ruplal House, Reboti Mohan’s House and Ahsan Manjil, remind of the former interdependence between the city and the rivers. They are concentrated in the old part of the city, characterised by a distinctively dense and rich tissue and its intricate network of alleyways and built forms.

3 villages and one fort

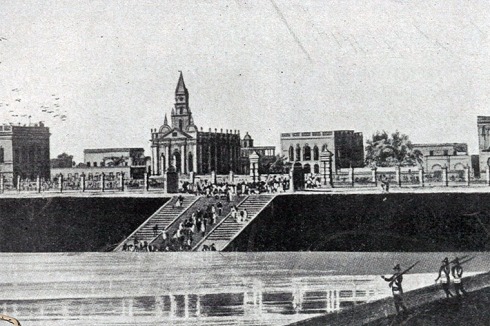

Though the British took the control of Dhaka, the prime city of then Bengal, only in 1765, their endeavour in the region started more than 70 years earlier, with the foundation of Kolkata. The River Hooghly, a western branch of the holy river Ganges, had been a traditional trade route in ancient Bengal, allowing business links with South and South-East Asian countries. The city of Hooghly emerged as centre of business during the medieval period, after the ancient trade capitals of Tamralipti, Tribeni and Saptagram went into decline. However, with continuous silting of the riverbed and engagement of larger trading vessels, port activities had to move further downstream. The British, who came to Bengal after the Portuguese, the Dutch, the Danish and the French, chose to set up a permanent trading post 40 km south of Hooghly. The birth of the city of Calcutta owes to Job Charnock, the British East India Company’s agent in Bengal, who in 1690 bought the 1692 acres [ca. 7 square km] of land formerly occupied by the three villages of Sutanuti, Govindapur and Kalikata.

The administrative district was set up within a small area only on the eastern bank of the river. On the western bank, the older town of Howrah was transformed by the emergence of factories and mill workers setting up shanty towns around them, but kept its own specificity and administrative autonomy in spite of the great economic interdependence with Calcutta. Differently from Dhaka, where the riverfront hosted both port activities and the elites‘ residences, Calcutta‘s riverfront in the 17th and 18th century was only used for loading and unloading of goods, movement of people through the jetties and dry docks for ship repairing. This separation of functions between riverfront and riverbank continued to determine the city‘s development and outlook. When, by the end of 18th and beginning of 19th century, Calcutta eventually became the administrative capital of the British colonial empire that extended over large parts of South Asia, the activities generated by the port remained restricted to the riverfront, while administrative, financial, banking and defence establishments occupied a large area close to Fort William on the riverbank.

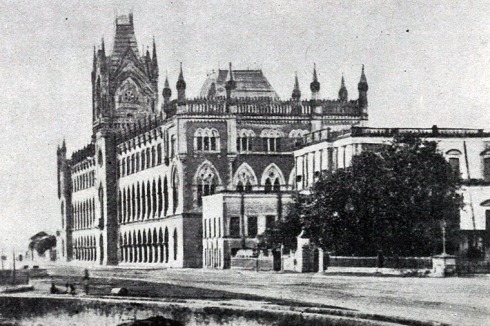

It is in this period that an 800 hectare forest area was cleared to make way for the Maidan [“open ground”], a large space for the army‘s drills. Dalhousie Square, the administrative district, was developed around a water tank nearby, and named after the Governor of Bengal, Lord Dalhousie. His residence was set up there too. It was just half km away from the river’s edge and office buildings for the banks, tea garden owners, jute mill owners and other trading companies were built around it. This very first “Central Business District” of old Calcutta occupied about 5 sq.km around the square. North of it, the native town – that is, where the local population used to live according to the then dominant urban model that foresaw segregation between the “white” and the “black” city – gradually developed.

An urban image in European sense started emerging with churches, avenues and vistas connecting buildings. As the leitbild was clearly shifting from a merchant city to the second capital of the British Empire, renowned architects and engineers were brought to showcase the British supremacy over the Subcontinent. The General Post Office (GPO), the High Court, the Treasury Buildings and even the Indian Museum established a new vocabulary of urban architecture coupling classical and gothic elements, which from imitating their counterparts in Britain progressively evolved into a distinct hybrid style.

Turning the back on the river

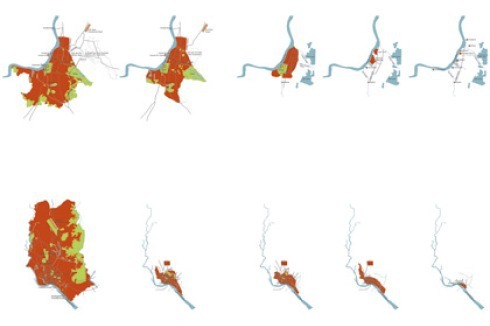

Despite the shifting of capital to Delhi in 1911, Calcutta kept growing: towards south and east, by gradually reclaiming low land and wetlands, whereby the big Salt Water Lake on the north-east fostered the traditional linear development alongside the north-south course of the Hoogly, at the expense of radial expansion. Towards north, urban sprawl connected the city with pre-existing small towns on the riverfront, resulting in a seamless conurbation that became known as “Greater Kolkata” more than 50 years later. As for Dhaka, its economic and physical conditions deteriorated heavily immediately after the British takeover, with population falling to as low as 26,000 in 1820. From early 19th century, it started to expand northwards as guided by the topography; the British brought in improvements like the construction of a protective embankment cum promenade along the Buriganga, instalment of a new administration complex and a university campus, until today seat of Dhaka University. A major commercial area extended both in north and east-west directions, along the two oldest roads; the south-north road led to military compounds as well as to the gardens of the Nawabs [Muslim rulers]. In the 1950s, latter area was developed as the main CBD, containing the President‘s House and the Secretariat, along with main sports arenas and commercial high-rises.

The different fates of the two cities – one founded and determined for more than 2 centuries by the British colonial power, the other shaped by most diverse rulers over a centennial history – do not overshadow their common features. These relate among others to the presence and use of water, especially of the rivers – the Hoogly and the Buriganga. Above all, considering only modern history, under and post the British the importance of the rivers declined in favour of land communication and its development measures, boosted by the advent of the railway and so called modern planning. The age of modernity in fact appears as one of increasing neglect of water courses. Interventions took place when the necessity to protect the settlements from water, during the monsoon but also after natural disasters, required engineering efforts. But the cities, busy at expanding horizontally (a process accompanied by far-reaching environmental transformations, for example through deforestation and filling up of wetlands), turned progressively their back on the rivers.

In Dhaka, the railway – linking to the 18-km-distant Narayanganj river port from the 1880s on and then gradually extended to connect the rest of the region – replaced the rivers as the universal way of communication. But the low-income groups, especially those from the riverine southern districts of then united Bengal, continued to value and use them. On the other hand, the maintenance of the khals was abandoned after the end of the Mughal rule, and they became unnavigable mostly by the late 18th century. From that time on, some of them have changed courses; others fell victim of siltation and encroachment. In the course of its rapid growth in the second half of the 20th century, the city continued to ignore the 17-km-long bank of the River Buriganga as well as the Shitalakhya, Turag and Balu rivers that actually surround and historically nourished it.

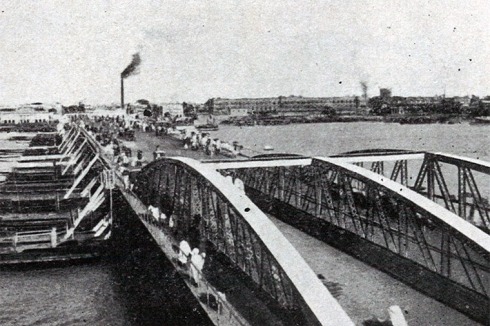

The railways heralded a shift in the movement pattern of industrial and agricultural products also for Calcutta, as moving people and merchandise proved to be now faster and safer. After the setting up of the first track in 1854 – with the train station being set in Howrah and not in Calcutta –, trading activities on the riverfront gradually reduced and other uses started cropping up at abandoned sites and warehouses. Earlier, the loading and unloading from ships required daily labourers, who came from the neighbouring states of Bihar and Orissa and settled along the river, wherever they got access to free land. When they became unemployed due to the decline of the shipping activities, they started to look for other jobs in the city, though not necessarily stopping living there. Thus the riverfront became the home of thousands of squatters foreign to the riverfront activities.

The common present: efforts for expansion and rivers‘ decay

The development of the railway was not the only reason for the decay of the rivers in modern times‘ Kolkata and Dhaka. Water in this delta and tropical region means both prosperity and menace – an ambivalence that underlies the special role it plays in many cultural manifestations, from rituals to festivals –, and this is mirrored by the sometimes contradictory interventions to handle it. Yet the main cause of contemporary degradation is the missing planning governance and failure of laws to implement necessary measures to cope with urbanisation.

The struggles for independence in 1947 led to the Partition of South Asia into two nations, India (with a Hindu-majority) and Pakistan (with a Muslim majority). Latter consisted of two separate parts, East and West Pakistan. Dhaka became the capital of East Pakistan, not only geographically but culturally and politically alienated from West Pakistan. Soon, an independence movement took form, which led to a liberation war and to the emergence of Bangladesh as sovereign country and Dhaka as its capital in 1971. While it had been able to bear the pressure of Muslim migrants coming from India post 1947, the city now succumbed to population increase, fuelled by the developments linked to a modern metropolis and capital city on the one and by unabated migration by impoverished rural people on the other hand. Between 1961-1974, population grew at a rate of nearly 7.1% annually, in the next decade even at 10%. In Post-Independence era, planning revolving around infrastructure and other provisions for the bulging population did not duly consider the environmental, social and economic roles of the rivers. Steady urbanisation, scarcity and high demand of urban land, unplanned expansion and lack of common civic decency all contributed to the gradual filling up of wetlands and floodplains, valued agricultural land as well as ecologically sensitive fringe areas.

Already in 1917, Patrick Geddes had proposed to revive Dhaka’s lost glory by means of rejuvenation of water bodies. He advocated improvement of the occupation-based traditional enclaves along the river and the preservation of open spaces and natural elements. The report alienated powerful citizens, and hence was not adopted. History seems to cruelly repeat itself. In 1997, RAJUK [Capital Development Authority] adopted the ‘Dhaka Metropolitan Development Plan’ (DMDP). Besides built up areas, the plan also included agricultural land and watersheds within its set of propositions for preservation and improvement. However, the absence of a detailed area plan until 2009 allowed unplanned and illegal growth, ad-hoc decisions and projects patronised by powerful quarters to continue. Planning authorities also failed to integrate Jinjira, a rural area on the southern bank of the Buriganga, already connected to Dhaka‘s old and new city by a bridge and avenue, which had been considered as a possible site for the Parliament post 1947 and could have allowed a more balanced growth on both sides of the river.

Post-Partition Calcutta experienced a quite different destiny. The city had already lost its role of capital city, but within the Indian federation, it additionally lost economic and political relevance. Between 1947 and 1951, the state of West Bengal was witness to one the largest instances of involuntary resettlements in human history, estimated to be 3.5 million of Hindu migrants from East Bengal, several millions more followed in the 1950s and 60s. Another spell of displacement occurred in 1971 following Bangladesh‘s Liberation War. The spatial organisation of the state, and especially of its capital city Calcutta, was strongly affected, whereby a huge number of people, forced to migrate from the economically depressed rural areas, added to this flow at least until the 80s. From the mid 20th century, Kolkata‘s industries located along the river progressively closed down due to the decline of congenial environment in Eastern India. The riverfront was largely occupied by migrant labourers and unauthorised occupants with no voting power. Hence it became a low-priority zone for politicians, keen to serve more promising vote-banks in other parts of the city. The Calcutta Port Trust, whose primary interest is confined to the management of the port and related activities, did not have the resources to administer such a large area of landed properties. Overlapping administrative jurisdictions and an impenetrable ownership pattern by different state and central government authorities resulted in lack of control; garbage dumps claimed most of the prime properties, encroachments of various types have been on-going.

An attempt to solve the impelling housing problem was initiated in the 50s with the conception of Salt Lake City, Calcutta‘s first planned township in modern history, by recovering the Salt Water Lake area. The project, which continued until the 80s, aimed at the same time to expand Calcutta’s breadth against its disproportionate length along the river, which complicated provision of basic services. The achievement of latter goal is still in progress and contemplates newer townships that are currently being set up or planned to the east of the city. Yet the idly realised housing scheme failed to provide dignified accommodation to the middle-class families, not to mention the poor. The riverfronts, both on Calcutta and Howrah side, continued to function as two orphaned children, surviving on leftovers and alms doled out by different authorities.

In the 1960s, the Calcutta Metropolitan Planning Organisation (CMPO), the Calcutta Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) and the Dacca Improvement Trust (converted to RAJUK in 1987) were established for planning and development of the Calcutta and Dhaka Metropolitan Areas respectively. However, none of them were able to prepare a comprehensive plan and the Hoogly and Buriganga riverfronts continued their unplanned, organic growth as the cities ignored them. After the turn of the century, the situation still appears beyond redemption.

0 Kommentare