Relegated to the fringe

Transformation of social and ecological space in contemporary Kolkata

Text: Dasgupta, Keya, Kolkata

Relegated to the fringe

Transformation of social and ecological space in contemporary Kolkata

Text: Dasgupta, Keya, Kolkata

Although Kolkata’s inner city offers sufficient areas for development, the growth has been centred on the periphery for decades. Many poor people also settled down in the surroundings of the wetlands at the eastern edge of the city. Since the land costs of undeveloped sites are rising rapidly, the city government is pressed by diverse interested parties to “clean up the mess”. In the result, the planned public housing projects in this area ironically do not only threaten the vulnerable ecosystem, but also the poor.

India‘s economic liberalisation is to this day affecting radical changes in cities via reform agendas and reframing of development policies. The Left Front coalition, whose 40 year rulership of West Bengal‘s state government just ended in 2011, has not been found to engage in any opposition of the Centre‘s liberal policy reforms. Rather, for example with documents such as “Vision 2025”, a Perspective Plan for Calcutta Metropolitan Area released in 2001, it has articulated the necessity to conform to the reform agenda by giving the private sector an important role in funding development and changing the role of the government to that of a facilitator, rather than a regulator and a provider. This is how, in post-liberalisation Kolkata, a spate of development projects funded by external agencies, national and international (like Asian Development Bank (ADB) or the British Department for International Development (DFID)), jointly with various agencies of the state of West Bengal, have defined the structure of urban governance, alongside with Public Private Partnerships focused primarily on real estate developments.

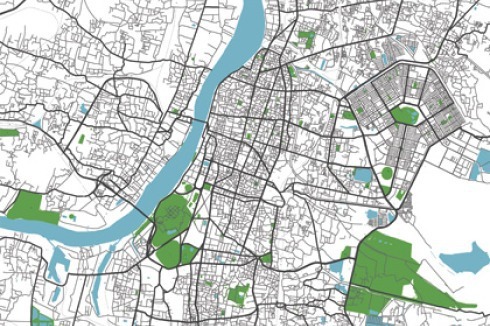

The task of developing the city was periodically assigned to a number of agencies that took decisions independently from and at times even against each other. Such segmented urban management reminds of Dhaka‘s context, where 42 agencies under 22 ministries “guide” urban development. Not differently from there, the political instrumentalisation of projects has led to a strategical stagnancy, causing in turn uncontrolled and uncoordinated growth. Yet peculiar for Kolkata is that this growth disdained the core city even though it offered scope and vacant sites for development and investment, and instead focused from the very beginning on the fringes.

Spatial reconfigurations: the city‘s escape from the river

In “Vision 2025”, one reads that Kolkata‘s ‘new growth should largely be channelised outside the metropolitan centre’. Such a principle is not the fruit of grounded reflections on adequate development models – e.g. supporting network cities and linear growth to de-congest the cores, as opposed to theories preferring compact cities –, but just puts up with a status quo that established itself in post-Independence Kolkata. Since 1951, population growth slowed down in the core wards and parallel to that, urban sprawl extended in all directions. It was so to say turning the back on the old city core, sitting on the idle Hooghly riverfront, whose perspectives of upgrading were not perceived, and looking for more promising, because hitherto unbuilt, spaces for development. For years ever since, the rate of population growth in the fringe areas far surpassed that of the core city. In the 70es, a planned city, ‘Salt Lake City’, was set up in the northeast, followed by the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass linking it to the airport in the north, to the core as well as southern part of Kolkata. With the E.M. Bypass ensuring excellent connectivity, most private investments in the post-reform period concentrated on the eastern fringes. New townships for the middle and upper-middle class, shopping malls and private hospitals started taking the place of the numerous illegal settlements and activities of urban poor.

In the post-Independence decades, in spite of violent political turmoils that plagued entire West Bengal all over the 1960es, the industrial and commercial network in and around Kolkata acted as a magnet for immigrant labourers from the neighbouring states and sometimes even further. Until the 1970es, the poor immigrants to Kolkata had actually settled in bustees, i.e. slum settlements, in the core area or immediately around it. These were recognised, i.e. authorised, and progressively provided basic services such as electricity and water by the Left government after its coming to power. However, due to space scarcity, the second and third generation had no alternative to crossing the thin threshold between tolerated and illegal occupation and becoming pavement dwellers or squatting on vacant land.

This is how, in the last three or four decades, unrecognised and squatter settlements have grown all along Kolkata’s fringes, on marginal land, along canals and railway tracks and pavements. All developmental projects in these very fringes took advantage from the illegal status of the settlements and pose clear challenges to their survival. Nowadays, as land values are rapidly rising, with a kottah [local measurement unit, equivalent to 67 square metres] of land next to the E.M. Bypass fetching Rs. 10,000,000 [around 145.000 €], several quarters are urging the Municipal Corporation (KMC) to “clean up the mess” – that is, removing the congested low-income settlements/slums along the bypass to allow redevelopment.

Kolkata‘s eastern fringes: current site of controversial development

The problematic aspect of these developments derives both from socio-political tensions linked to land acquisitions, disappropriation and resettlement of urban poor on the part of the state and from environmental concerns, as all mentioned projects are taking place in the immediate proximity of, and increasingly on, the East Kolkata Wetlands. Wetlands are transitional lands – between terrestrial and aquatic systems, with low water levels. They are a constituent part of the mature delta of the Ganges and spread over low-lying lands all over Bengal – Dhaka for example used to be surrounded by wetlands both to the east and west. Salt water lakes and swamps originated by the earlier incursions of tidal flow from the Bay of Bengal define this ecosystem. Still nowadays, the East Kolkata Wetlands receive one third of the megacity‘s drain water. Extreme solar radiation makes algae and plankton grow, which in turn provide nutrition for cultured fishes and function as natural purifiers of the water, used for the irrigation of the near rice and vegetable fields. In short, the wetlands represent a unique example of locally adapted functional uses supplying Kolkata with fish and vegetables, thereby providing occupation to 20,000 up to 40,000 people.

A High-Court decision established that no further construction shall be allowed in this precious landscape; since 2002, the East Kolkata Wetlands are listed as a wetland of international importance by the Ramsar Convention, which commits the member countries to conserve them. However, in 2006 filling up activities alongside the bypass were observed; to date, encroachment is ongoing in spite of all laws or policies. Over and above, many public-private ventures have been coming up. Controversial debates around the overall policy the state should adopt – from radically stopping any construction, to supporting a controlled development, or definitely releasing the entire area for development on account of the scarcity of alternatives for the necessary urban growth – haven‘t yet led to a resolution.

Urban renewal under state control?

In this already complex scenario is now interfering a large public sector-initiated and funded project from the central government, that is, from Delhi. With the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), promising Rs. 125 billions [ca. 2 billions €] to 63 chosen cities in the initial phase, one of the most prestigious projects in India‘s Urban Reform Agenda took off. It comprises of two sub-missions, Urban Infrastructure and Governance (UIG) and Basic Services to the Urban Poor (BSUP), with the largest share of the funds allotted for the former. The rationale of the program, as many observers have critically pointed out, is that cities are currently inefficient both in raising resources to meet their growing needs and in governance, hence they shall be bailed out with funds to meet their infrastructure needs – on condition that they carry out certain governance reforms, which will make them self-sustaining and efficient. In other words, urban sector reforms shall from now on follow economic reforms.

With this, the JNNURM does not stand on its own. From its very conception, it was well entrenched into the Tenth Five Year Plan (2002-2007) that integrated housing, transport, slum upgrading, environment improvement, structural reforms and public-private partnerships into commercial profits. The currently ongoing Five Year Plan furthers the same development strategy. For the first time in India‘s urban planning history, which was based on a separation of functions between the central and state governments – with the first framing macro economic policies, the second responsible for implementation –, grants from the Centre are contingent upon a chain of reforms, both optional and mandatory, at the local level.

The paradoxes of formalisation

In Kolkata, a number of large and densely settled slums in fringe areas have been selected by the Municipal Corporation for the implementation of the JNNURM’s BSUP projects, but in particular way the eastern fringes. The ongoing redevelopment is mainly consisting of demolishing the present settlements, generally one- and a few two-storied buildings, and building multi-storied flats, while keeping the excess land for infrastructural or other basic uses. Especially residents entertaining informal activities at the ground level, for example vendors with their carts or rag-pickers, are affected by such changes since after upgrading, no space is left for them. One could cite numerous cases in Kolkata, and in most other metropolises in India, where poor migrants have settled in state-owned land over the last four or five decades and enjoyed basic services and voting rights as part of the then still dominant welfare mentality. Such is now replaced in the main by an exclusionist agenda in the garb of ‘development’. Paradoxically, formalisation – a goal that the State envisaged with the JNNURM – here becomes a threat to a vulnerable group of society due to a lack of will to factually empower them.

In this context, the implementation of the programme raises serious concerns. In Kolkata, till date none of the procedures charted out within the BSUP programme – expected to encounter the needs and enforce participation of the urban poor – have yet started, and residents of most sites have not been informed or consulted on what the project entails. Furthermore, only those who have some sort of document to prove tenurial rights would be considered for resettlement, while the rest of the settlers would remain out of the programme. Once resettled in flats, tenants are expected to bear maintenance costs, which many are not ready or capable to pay since, until today, basic services were given for free by the government. Another problem is that, if one reads between the lines of the agreements being handed over to the stakeholders, in most cases the flats are given on long-term leases under condition of payment of part of the costs, yet not comprising any ownership rights. This is due to the fact that a legally defined resettlement and rehabilitation policy by either the Central or the State government is to date missing. Precisely here, the actual core issue that no one is willing to tackle arises: if land tenure – which, by the way, has been enlisted among the entitlements of the BSUP – is not addressed, the urban poor will continue to be excluded from humane housing conditions.

New emerging politics of space

Yet in this picture, citizens are not only victims, but are progressively taking initiatives. The current development‘s impact on space, society, economy and also polity is lately being assessed, apprehended, and made to the basis for an emerging critique at the ideological – with book releases and vivid public debates – and (grass-)root level. Let‘s take for example Hatgachhia I. This area of approximately 61.000 square meters near the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass, along a prime high land-value area that is meanwhile occupied with hotels (one a seven-star), luxury apartment blocks, a permanent exhibition complex, the Science City – and various similar developments planned for the future –, has been earmarked for the initial phase of redevelopment in JNNURM’s BSUP programme. Its first settlers, mostly cultivators, claim to have bought plots to build houses and land to cultivate already 40 year ago. Today, against the municipality‘s claim of ownership over the same lands, the dwellers display their revenue documents to fight against redevelopment. Since a residents’ collective, Hatgachhia Bustee Unnayan Committee, has been resisting for the last few years, the provision of basic services by the Municipal Corporation has been cut. In the meantime, some of the residents of the adjacent locality, evicted under the promise of resettlement, have gone to court, out-of-court settlements have taken place, NGOs and civil society groups have joined.

Similar emerging movements – at very local levels, often unplanned, undefined, spontaneous – in Kolkata and in other places in the state of West Bengal have defined forms to claim for what is increasingly perceived as the right to city space. Vis-à-vis the new development of urban India, a new kind of politics is taking shape, in which non-party political groups, associations, initiatives of affected people with support from members of civil society join forces beyond and in opposition to the old protagonists of political representation, i.e. political parties and trade unions, forming a strengthened resistance.

0 Kommentare